PHILIP EVERGOOD, An Overlooked American Painter: Moments of discovery are so fascinating because you are suddenly caught up in something unexpected: over the course of a career here a few names and artists discovered beginning in the mid 70s till today. My art sleuthing has led me to such artists as Jackie Ferrara, Robert Longo, Cindy Sherman , Franz Erhard Walther, Ulay/Marina Abramovic and Damien Hirst . Today recent discoveries and rediscoveries. Include these five women to follow: Katherine Porter, Max Cole, Maureen Dougherty , Sally Davies and Tracey Snelling (if you can never get enough art!). Three were collected for the Microsoft Art Collection in the early 2000s.

While researching the history of the Terry Dintenfass Gallery for the exhibition, The Women Who Made Modern Art Modern, an exhibition I organized back in 2016, I was introduced to the work of the painter Philip Evergood. Perhaps re introduced to his work is a better way to explain this event, having been in the Whitney ISP program many years earlier I knew one of his classic paintings in the museum’s permanent collection, Lily and the Sparrows –1939, a work that always intrigued me because of its psychological intensity. This was painted in the fall of 1939 just as the war had erupted in Europe. She is a girl seemingly locked into her red brick world-a foretelling of the Anne Frank story-who watches as sparrows fly freely before her open window. Freedom is there just outside her window but now not reachable.

Likewise the painting, The Future Belongs to Them–1938/52, now in the collection of Terry’s son Andrew and his wife Ann, is quite remarkable in that it is a mature visual statement coming after the painter’s years studying abroad who is now building a life and career in New York. It is also one of Evergood’s largest canvases– a masterpiece as both story and image. This is an honest and heartfelt representation of a woman holding onto a number of babies of different colors and races. She is the absolute representation of a tolerant world, a world in which all have opportunities to grow and thrive. She is mother and heroine both modest and proud. She is a beacon of hope in the world of 1938 — one year away from the outbreak of WW II and all that it destroyed. Evergood painted it in 1938 and then further embellished it in 1952.

For many the question asked is simply, who is Philip Evergood? I had wanted to answer this in the form of an exhibition, and what follows instead is the beginning of an essay. And you ask why? He is a significant artist in the history of American art who has been sorely overlooked. His work connects to the political and social climate of today even though his works date back to the 30s– the years of the Great Depression. Yet we are now confronting some of the same issues as then: a political crisis in our government, the likes of which we have not seen before; economic imbalance, mass migrations caused by war, issues of race and inequality in our society, and extreme weather events causing floods and droughts. By the time Evergood had finished his beautiful image, Mussolini had been in power since 1923, Hitler since 1933, and Franco of Spain the next year. War was to be everywhere which became a preoccupation of Evergood’s, exemplified by the intimate portrait of a badly wounded young boy who survived the siege of Stalingrad. The daily life of those on the battlefront and those surviving in cities across Europe are tied up in the portrait of a young Russian depicted in the 1943 painting, Boy from Stalingrad. Akin to Otto Dix’s portraits in graphic reality of wounded soldiers of WWI, Evergood presents to us not the heroes of battle but the victims of such violence. The battle for Stalingrad was a major event in Hitler’s plans to invade and conquer Russia. It ultimately failed but at the cost of thousands of lives.

Deep in the archives of WNYC radio, one will find a 1944 interview with the American artist Philip Evergood. (Self Portrait in Straw Hat). The interview is conducted by his long time friend and colleague, the painter Frank Kleinholz. Evergood was invited to participate in a weekly radio program and was asked to define his philosophy when it came to painting. Evergood was quick to explain that he had just completed twelve images for the Russian War Relief Calendar, a calendar used to help raise funds for the victims of Russia’s battle against fascism. Evergood, very proud of his work and his contributions to the relief fund, was clear to explain that he saw himself in a long tradition of humanist painters, those artists who like Rembrandt or Brueghel represented aspects of the human condition. In fact six years earlier in 1938 he wrote that “great art lives because it has universal human appeal.”

For Evergood, the follies, foibles and actions of men and women were the focus of his life’s work. Contemporary life as represented in his paintings across some five decades was a statement about the values, concerns and actions of humanity. It was the story of people living in the 20th century.

And while other painters in this modern era as diverse as Philip Guston, Jacob Lawrence or Leon Golub have become recognized and championed for their social awareness, it is Evergood who represented these causes over the course of his life and in depth through paintings, works on paper and prints ( Waiting Room,1936). And these causes, whether it is freedom, liberty and equality; are, still today, of keen importance for our society. We witness the same struggles with the issues of social justice, economic equality and the security of our democratic system of government on the internet and in social media, and before the impact of technology was the impact of painting. 75 years ago in the war year of 1944 all three characteristics of a free and open society were under attack by the forces of fascist regimes as in many ways they are similarly under attack today in the form of racism, bigotry and economic disparity. I would argue that Evergood’s images from the past are extremely relevant today; though the painting style we see is different, the images reflect today’s very complex and very conflicted social order. For example there is (Home, 1946 ).

Lost among the many ongoing developments and overlapping movements of the post-war art generations, Evergood has been off the art world’s radar for many decades. With no heirs or foundation no one has been charged to keep his works in the public eye. In fact, his last solo show at the now closed Kennedy Galleries was in 1972. Yet this American born and English educated artist has much to tell us; to share with us and can stand as a model of social consciousness and an innovator in the visual arts.

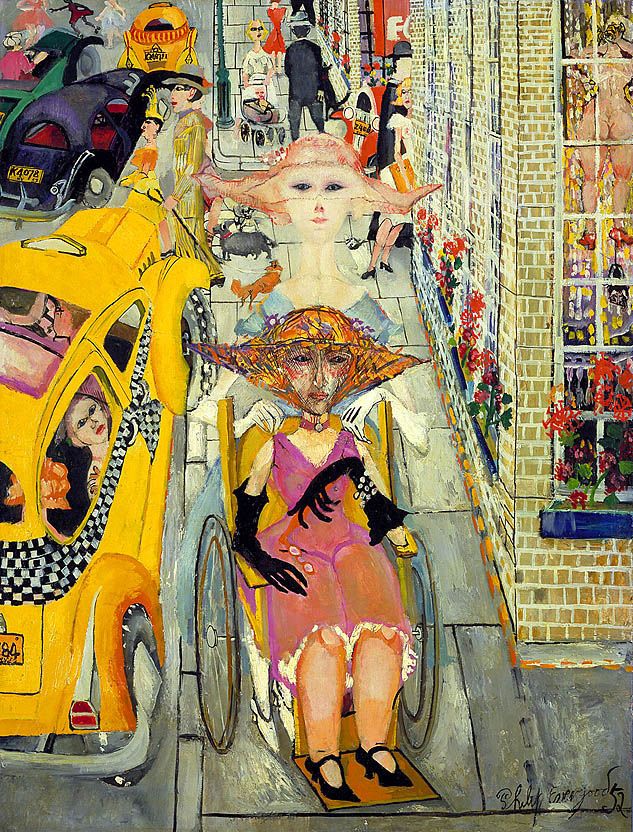

His idiosyncratic if not peculiar style seems to be an amalgamation of an expressionist drive with some of the hard edge reality of Germanic painters like Dix and his contemporary Max Beckmann. Evergood’s figures are crude at times, beings twisted and bent by poverty, war and fate. He is a great chronicler of American society in the pre and post war eras; those living in the countryside ( The Lake ) or those living in the city. (Sunnyside of the Street ) A Corcoran Gallery of Art prize winner that was then purchased by the former museum in 1950. In Artnews, the reviewer noted ,” a lively street scene by Evergood which is one of the outstanding paintings in the show.” The street is a meeting place for kids, black kids who play stick ball, hopscotch, the street is the playground for the neighborhood. But in this neighborhood too lives a blind man, a child in a wheelchair and in the distance an ambulance arrives for a patient. This was typical of Evergood to present us with all aspects of daily life.

Children are his heroes; they live in an idealized world not yet affected by conflict. Families are his barometer of a happy life and an equally happy future. In spite of the horror, terror and calamity of war and economic hardships of his middle years, Evergood largely remained an optimist.

He had a taste for romantic things, symbols and images of a world made up of fancy and fantasy as much as of the ordinary day to day, borrowing from literature and history to describe and represent the present. Though he never served an avant-garde such as the younger generation of painters developing around him, nonetheless he saw himself as a significant maker of images and pictures whose virtues were the constant examination of human interests, desires and tales. (Boy Eating Pear) ; and the Smithsonian’s (A Woman at the Piano).

“I am a social painter,” Evergood remarked in an article of the same title in the Magazine of Art in 1943. Like his uptown New York contemporary, Alice Neel, much of Evergood’s social painting was born from his domestic situation. His dancer wife, Julie, was partner, model and muse. Though the couple had no children of their own, children remain important characters in his work, representing youth, hope, fraternity and the future of society as suggested by the title of that early painting The Future Belongs to Them 1938/52.

An exhibition of his work right now would bring some fifty years of this truly American painter and commentator back into the light of a 21st century discourse. From his pictures of crowds, women, and children we see a painter who recognizes the power in the people; in the portrayal of an innocence and the noble character of the modern woman. There are images of crowds who are the players in the world’s drama. From social realist to imaginary realist, the figure was key to Evergood’s paintings and his figures could be elegant and reserved or crude and suggestive. Both represent the extreme of humanity, the heroes and the victims of war, strife, or difficult economic times; those who survive and those who falter. Has anything about these protagonists changed since Evergood put brush to canvas and began to exhibit his works?

“Philip Evergood,” wrote Alfredo Valante curator for his 1969 solo exhibition at the Gallery of Modern Art in New York, “has remained a proponent of sympathetic analytical views of people and their problems, a visionary interested in their dreams, theirs hopes, their tragedies.” Evergood’s life ended suddenly in 1973. He died in a small fire in his home in Southbury, Connecticut. Fate had extinguished a long career that had led to a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1960 at the age of 59 with the support of many of the important collectors of his day including Joseph Hirshhorn who collected some 68 paintings and works on paper over a 30 year period. Nevertheless, Evergood gets short shrift now. When included in the 1991 Museum of Modern Art’s Art of the Forties, he is published between the pages of Ben Shahn and Jacob Lawrence and he is represented by a single print, hardly fitting for a painter who decades before garnered significant attention and awards.

Evergood is never billed as a modernist and he is pigeonholed as a Social Realist which casts him in the light of being Socialist, Communist or subversive. One might argue that the mercurial nature of his works, his deeply romantic position and his political ideals as a painter puts him ahead as an early Modernist in the tradition of Van Gogh or Gauguin more than the tradition of Rothko or Newman. He is painter, a poet of the people depicting strife as well as pleasure. His paintings are intimate, easel size, distinct vignettes. Over time he was more and more on his own far afield from the trends of Abstraction Expressionism, or Pop Art and Minimalism.

He is an exile at home followed by a small but loyal crowd led by Herman Baron, founder of the ACA Galleries and longtime friend, and John Baur, former Director of the Whitney Museum who followed up on his 1960 catalogue for the artist and wrote a lengthy monograph on Evergood published in 1975 two years after the artist’s death. Baur summed up Evergood’s sensibilities this way, “He had to weep or laugh in life with the same intensity that he wept or laughed on canvas. And he had to translate the emotions of life into the very different languages of art with the utmost intensity of feeling.” In 1966, critic Lucy Lippard wrote at length for a monograph focused on Evergood’s array of drawings, studies and prints. For Evergood his painting or drawing style was subject to need, desire and ultimately to the end product of his search for meaning through the invention of highly imaginative pictorial narratives that drew from sources close at hand including friends, families and colleagues. “The work of Picasso and his outstanding contemporaries Braque, Rouault, Matisse Chagall has substance and meaning no matter how experimental it may be,” says Evergood. Similarly, Evergood saw himself free to experiment to create the paintings that worked best for him.

Painting was a form of storytelling. In an unpublished essay of the 50s. Evergood said “Realism means being concerned with this world, expressing emotions common to all mankind. Realism to the artist, is the expression and interpretation of his experience.” It is an examination into the moral and ethical character of men and women, young or old, black or white, at work and at play, at peace and at war. His was an encyclopedic overview, an examination of the human condition not as a judge but simply as an observer. His observations could be close and detailed or far and fanciful as if in a dream. These extremes that are now accepted as concepts today were not so much in his heyday. Look at painters such as Squeak Carnwath and Charles Garabedian and even the late works of Grace Hartigan; or others like Malcom Morley and Jonathan Borofsky—figurative invention is their way to find meaning.

Over the years other writers, critics and artists have expressed their support too: Manny Farber, Fairfield Porter even Jack Tworkov, a leading member of the Abstract Expressionist group, painters whose aesthetic was in direct opposition to Evergood’s humanist beliefs. As a painter in his own right, Porter’s profile in Artnews in January1952 he describes Evergood’s techniques and materials in detail, focusing on the mechanics of getting the image on the canvas having studied the subject. The final painting,Girl and Sunflowers, is a classic Evergood which depicts a young girl surrounded by giant sunflowers making numerous charcoal drawings. We see the creation of a romanticized landscape where youth is secured and surrounded by natural beauty.

In the hands of art historians, critics and curators who understand that the history of art is not a static history but a dynamic one which needs constant attention, the past is reexamined and its relevance to the present made clear. Evergood deserves a place at the top of the list.