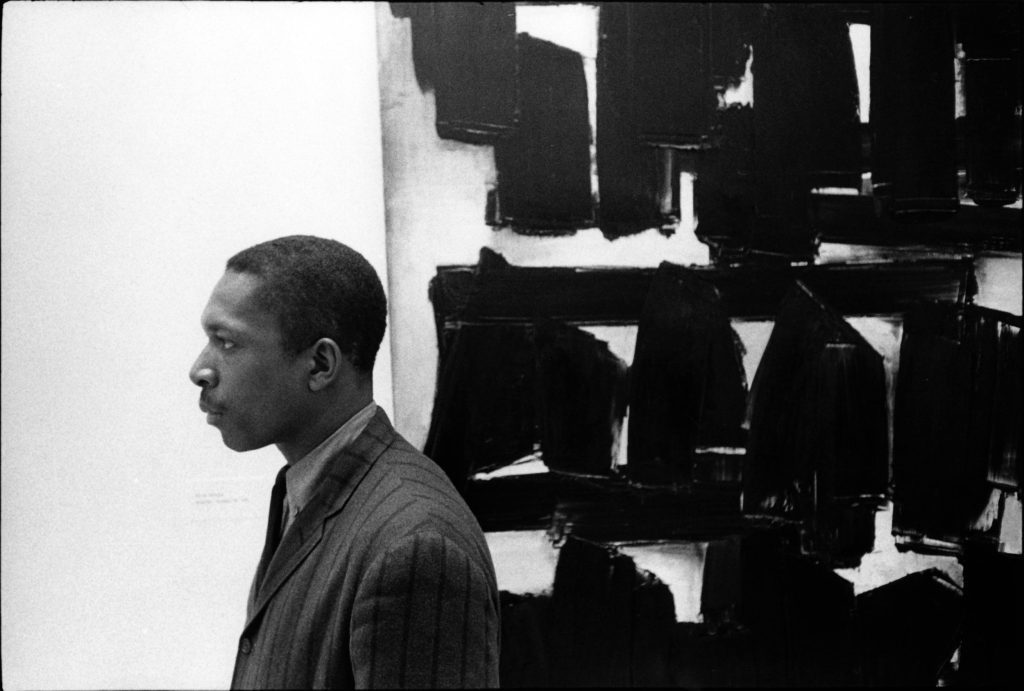

Some years ago, at an Art Basel Miami art fair, I saw a small 1999 painting by Pierre Soulages in the booth of a German gallery. I was in Miami looking for works for the Microsoft Art Collection, a collection I had been hired to expand and curate the year before.

It was 1999, and I wondered, ‘Is Soulages still alive and working?’ He was part of a post-war group of abstract painters who had survived the war and were much heralded in their respective countries. Each had his own brand of creativity and invention. Soulages, born on Christmas Eve in 1919, was then 80 years old when he presented this work. He died in 2022.

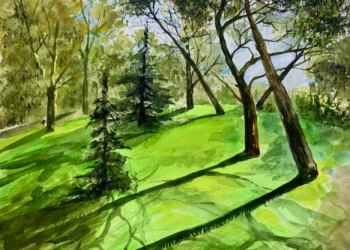

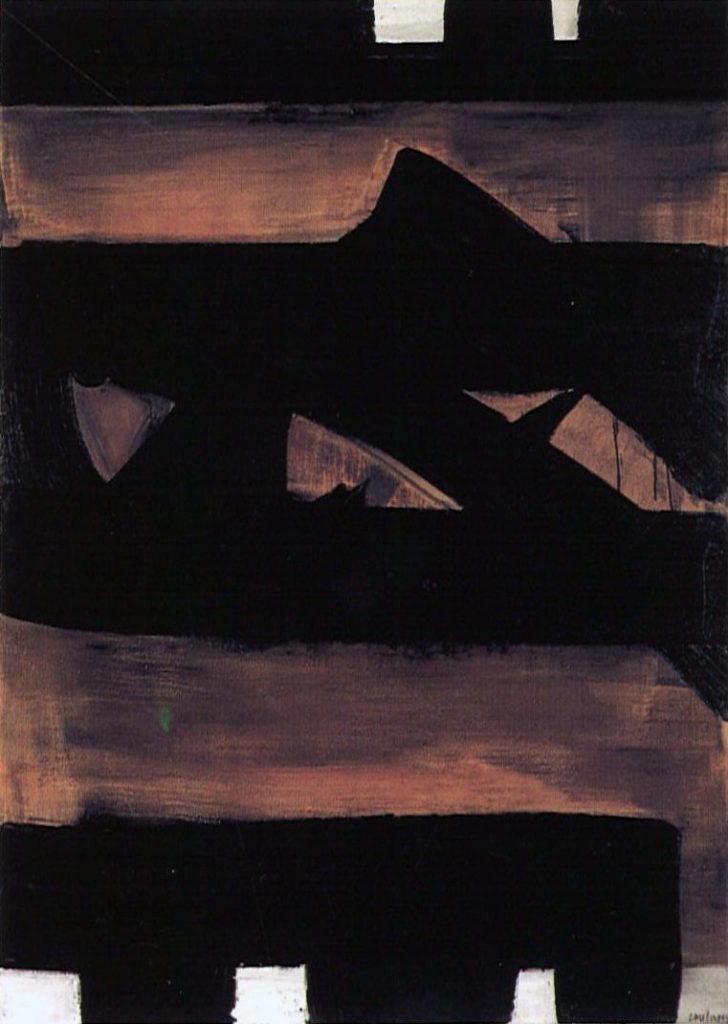

The small painting, all black, was stunning, no larger than 20 x 30 inches. Universally applauded, Soulages was a French artist whose thick black brushstrokes—labeled outrenoir (beyond black)—against lighter backgrounds characterized his eight decades of work. A painter so opposite the two schools of painting that dominated the French landscape: Impressionism and Fauvism, both renowned for bright colors and endless displays of life in broad daylight, and au plein air. Here was a painter who chose a monochromatic path as if rejecting anything made by the two masters of Modernism, Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, and finding his own path and way.

A solo show in New York opened in the spring of 2014, ‘Soulages in America.’ A friend and artist, Mark Petersen, flew from Oakland, CA, to see this show with me. Mark, also an abstract painter whose work I had discovered online the year before and had bought two paintings for my collection, died way too early in 2019 by suicide.

We both agreed the exhibition was stunning, dramatic, and well-installed, so we spent an hour or so wandering from canvas to canvas. Surprisingly, the gallery was not busy, but again, this is not everyone’s taste: all black paintings. But the drama was in how they were made and how light reflected off the surface of each canvas. Decades before the post-minimalist movement in the US, painters in the post-war era were engaged in all sorts of experimentation with the meaning, content, and substance of painting. Turning inward, they looked away from the city or countryside, still scarred with the wounds of World War II.

His first dealer in New York, the highly influential Samuel Kootz, took Soulages into his gallery in 1954 and worked with him until the close of the gallery 12 years later. Kootz, one of the leading art dealers of the post-war period in New York, was an early supporter of the American school, including Franz Kline and Willem de Kooning. Kootz was also aware of and a champion of the post-war advances in painting in Europe. Almost a decade later, James Johnston Sweeney, another early supporter, organized a Soulages retrospective at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in 1966.

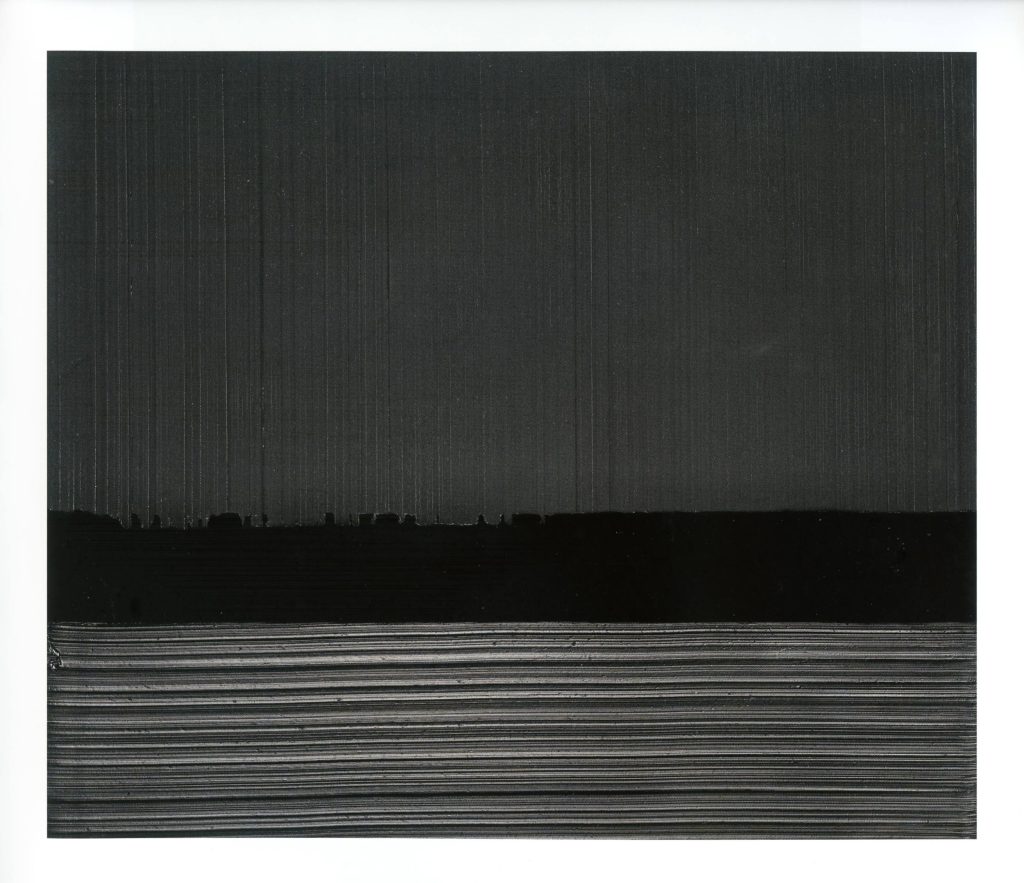

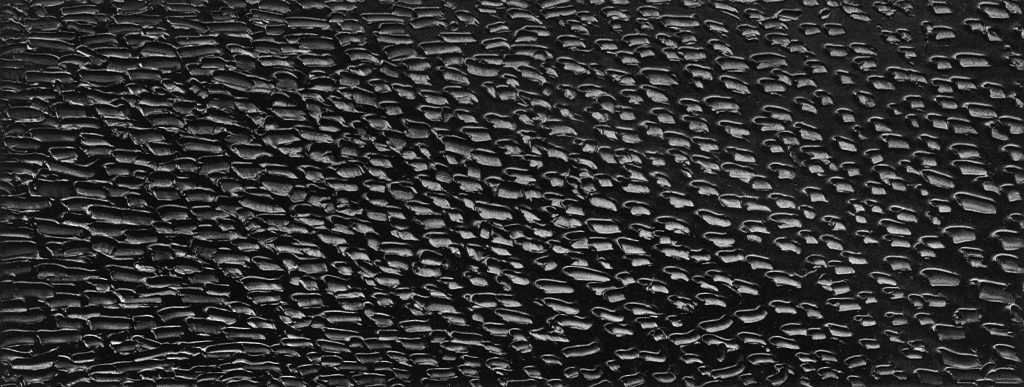

Some might compare Soulages’ works to Frank Stella’s black paintings of the 60s, but Stella was more formulaic, depending on shape and structure rather than invention and emotion, and the drama of executing such ultimately elegant compositions. Initially, the black element was the persona of the painting, placed in front of a monochromatic background. Over time, the black became dominant, encompassing both the foreground and background. And over time, Soulages explored a textured surface. Here, Soulages examines the very nature of the medium: how to guide it and apply it onto the surface of the canvas.

Ironically akin to artists like the Italian Piero Manzoni or the American painter Robert Ryman, both of whom chose white as their color. Like Ryman, Soulages saw painting in terms of process, thereby exposing the dynamic character of paint as a way to see each work not as a window to the world but as an object that exists within the world. Each work is a fully formed and shaped matter of canvas on which a systematic application of paint is made. And while united by paint, the nature and character of each canvas changes and shifts depending on scale or the pattern of paint application.

When Pepe Karmel published his ‘Abstract Art: A Global History,’ I wondered how Soulages and his circle would be discussed in the context of abstract painting around the world. Much to my surprise, he was not included, nor were his German contemporary Hans Hartung, or Americans like Grace Hartigan or Jack Tworkov. The focus for many curators and art historians over the decades of the 60s, 70s, and even 80s was towards movements like Pop art, Minimal art, and Conceptual, pushing European avant-garde innovators aside. This also explains why Soulages was not offered any other museum shows in the US since 1966. Yet times are changing. The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, in the fall of 2015, presented a retrospective of the post-war Italian artist Alberto Burri, an eye-opening exploration of the growth and manner of another painter who experimented with a variety of materials and, in his late years, monolithic paintings in black.

This second show at Levy, Gorvy, Dayan, and is an important event, a selection of some 30 works from local museums and the artist’s studio. It is a recognition of his masterful talents and hard-won vision.

‘It is everything a collector would want to find in a Pierre Soulages, from the bold, energetic composition to the play of light and the sensual interaction between the black and blue paint,’ as opposed to Kline’s intersections of black strokes and fields.

In his native France, Soulages donated some 250 works for a museum opened in 2005 and dedicated to his life and work. The museum is in Rodez, France, near the city of Toulouse.

‘Soulages should be known and honored in this country as we now honor the masters of the Abstract Expressionist movement. Soulages proves the power and passion of abstraction. He has distilled the essence of painting, albeit painted at midnight.