By Berfin Cicek, Artist & Gallery Director, Founder at Cicek Gallery

February 10, 2026

There is a particular economy to Tayisiya Shovgelia’s work – not an economy of restraint but of insistence: she insists that feelings be taken seriously. In canvases that at first read as intimate and painterly, and in live performances that turn process into choreography, Shovgelia stages a recurrent question: how does painting – a medium often accused of self-indulgence or aesthetic insulation – make room for collective pain and consolation?

Tayisiya’s practice is shaped by a migration from the life she knew in Ukraine into London’s brittle warmth. That dislocation is not dramatized; it is folded into the surfaces of her pictures. The palette moves between bruised reds and the fragile glow of candlelight; gestures alternate between hesitant, almost apologetic strokes and sudden, decisive cuts of paint. In describing the origins of her visual language, she returns to a childhood moment – a hedgehog drawn “like a sausage with needles.” The memory makes her smile, but the sketch became a quiet talisman: a lesson in embracing the awkward and the imperfect, and in finding beauty where it’s least expected. It’s a minor childhood episode, but its presence is telling; her work is equally interested in the awkward, stubborn persistence of memory and in the ways minor humiliations and domestic stories can become the seeds of later artistic honesty.

REINFORCE (2022), her solo project in Clapton, is the most explicit attempt to translate a private trauma into a public and generative form. The show was less a gallery of finished tableaux than a program for communal repair: a central live-painted tableau worked as a kind of anchor, explicitly designed to knit together other pieces and to create a space where displaced Ukrainians might “feel a little more at home.” That civic ambition — art as infrastructure for feeling — is not sentimental. Where many politically-oriented shows fall back upon slogan or spectacle, Tayisiya’s work remains formally rigorous. She lays down the background and basic composition before the performance — a quiet preparation that lets her trust the canvas, so the live moment can respond to the room instead of being drowned out by it.

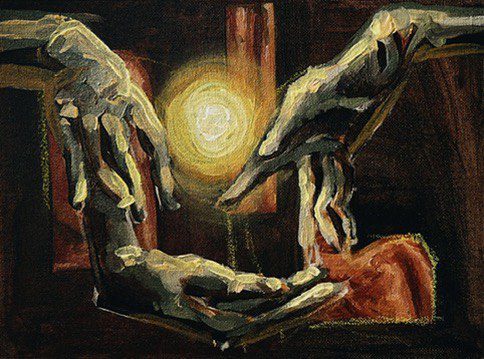

The live performances, especially those with the jazz-electronic act Respair, are revealing. Tayisiya has a keen sense of the synaesthetic affinities between sound and mark-making: music sets the tempo and emotional register of her brushwork. There is an admirable humility in this — an admission that painting can be reactive rather than sovereign. Her gestures become a kind of notation of the evening’s affect; wide, chaotic strokes register panic and loss; tighter lines and delicate smudges are gestures of care. Crucially, she preserves evidence of process — fingerprints, scraped layers, traces of previous compositions — and in doing so allows the viewer to feel time pressing through the surface, as if the work has lived before you even arrived.

Technically, the paintings achieve their effects through layering and subtraction. Tayisiya builds and then reveals: thin washes sometimes expose the raw canvas beneath, as if to insist on the fragility that underwrites every psychic architecture. Colour-loaded flesh — the artist’s frequent subject — is never purely figurative or portraiture for its own sake; faces and bodies function as loci for affective transmission. The paint is often applied with a mixture of urgency and tenderness, the surface both wounded and offering light. When she speaks about “painting more love” and about a candlelight project intended to make viewers “feel warm and hugged,” this is not an anecdotal turn to cozy themes; it is a formal strategy to counterbalance the abraded and exhausted registers elsewhere in her work.

For all of these strengths, there are moments when the narrative aim — to be a vehicle for collective healing — risks flattening complexity. In works where the social purpose is foregrounded, the painterly subtlety can be attenuated; the invitation to the audience to “participate” sometimes becomes, inadvertently, a shorthand for empathy. The best of Tayisiya’s work avoids this pitfall by insisting on the singularity of sensation: ambiguity remains, and the viewer must do the labor of recognition. Her most persuasive pieces are those that refuse easy consolation while still offering tenderness.

Where Tayisiya distinguishes herself from many contemporary artists is in the moral seriousness of her practice. Vulnerability, she insists, is not weakness but an ethical stance: it is the willingness to let emotion remain visible, even if it is that messy. That posture – and the formal methods that sustain it – mean her work will inevitably occupy a contested space between therapeutic art and critical art. That tension is productive; it keeps the work from turning into either didacticism or pure catharsis.

Looking ahead, Tayisiya’s desire to move beyond the canvas into immersive and participatory formats is welcome. If she can maintain the formal skepticism that animates her best paintings while enlarging the site of affective exchange, she could point the way toward new, honest ways of using art to respond to trauma – ways that don’t feel too exploitative or inward-looking. For now, her paintings and performances offer a compelling argument: painting can still be a language for the unspoken.