By Berfin Cicek, Artist & Gallery Director, Founder at Cicek Gallery

December 19, 2025

Displacement has become one of the defining cultural conditions of our time. Yet within contemporary art, its visual language is quietly evolving. Where narratives of rupture and loss once dominated—often through direct or confrontational imagery—many artists are now turning towards reconstruction. Not the erasure of trauma, but the slow, attentive rebuilding of inner coherence through place, rhythm and continuity.

Landscape art, particularly in its abstract and symbolic forms, has emerged as one of the most effective tools for this process. It allows artists to explore identity, belonging and cultural memory without relying on literal narratives of suffering. Instead, it offers space—emotional as much as physical—within which new relationships to self and environment can form.

Nature as a Relationship, Not a Motif

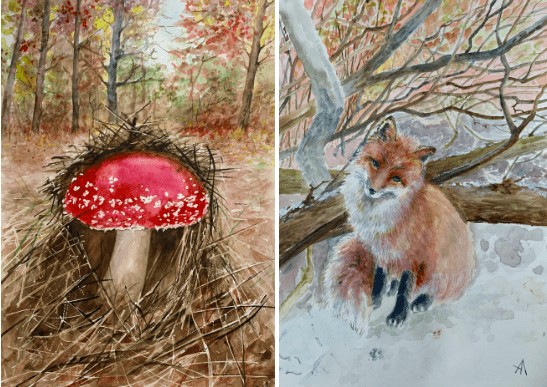

For artists who have experienced displacement, nature is increasingly treated not as subject matter, but as a stabilising presence. Engagement with landscape becomes an embodied practice: walking, observing, returning, translating. In this context, nature is neither decorative nor nostalgic. It is alive.

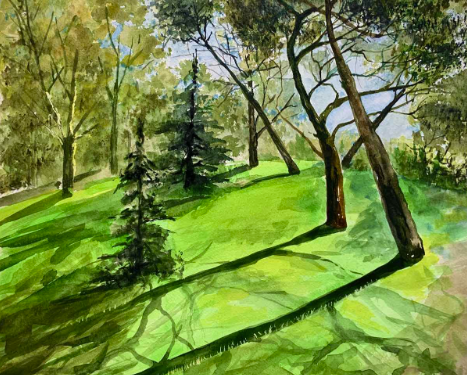

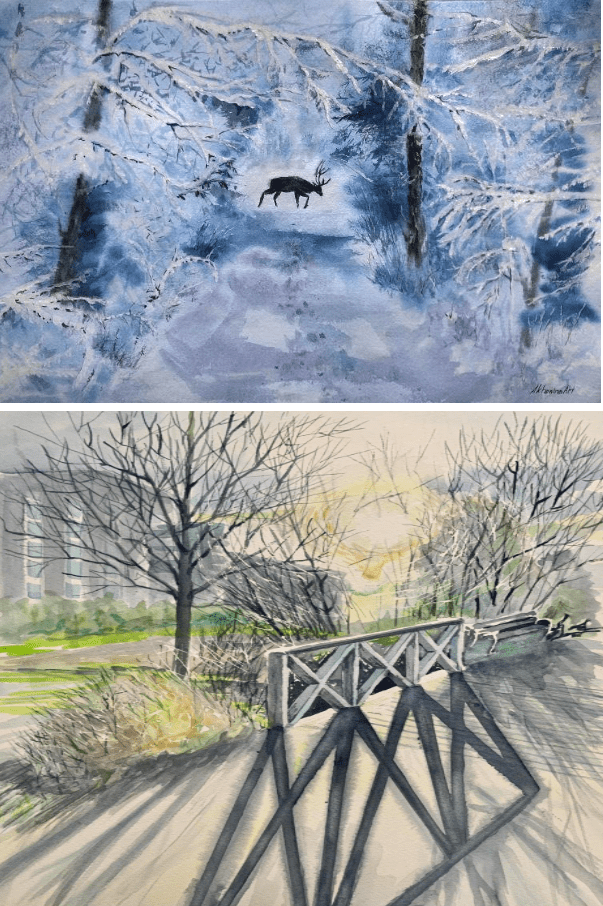

This approach is evident in the recent work of Ukrainian-born, UK-based artist Liudmyla Akhonina, whose nature-driven paintings reflect an understanding of the artist as part of a wider ecological and emotional system. Her repeated return to trees, grasses, mountains and coastal forms suggests a relationship with landscape that is participatory rather than observational.

Britain’s varied countryside, urban parks and mutable weather have provided fertile ground for such practices. For artists arriving from other cultural contexts, the British landscape often offers a form of quiet hospitality—one that does not demand explanation and allows time for recalibration.

Finalist, Wales Contemporary 2025

Finalist, Wales Contemporary 2025

From Fragmentation to Continuity

Displacement is rarely experienced as a single break. More often, it manifests as fragmentation: a sense that identity has been scattered across places and timelines. Landscape-based abstraction offers a way to gather these fragments without forcing coherence too quickly.

In Akhonina’s case, this process became particularly visible through her engagement with Wales. Following her participation in Wales Contemporary, she began exploring the Welsh landscape more deeply, eventually exhibiting at the Pensychnant Conservation Centre. The visual parallels between the Welsh mountains and the Carpathians of her native region became a quiet bridge between memory and present experience—one that resonated strongly with local audiences.

Here, abstraction functions as an ethical choice. Rather than illustrating displacement, the work allows multiple geographies to coexist within a single emotional field.

Cultural Memory Without Spectacle

There is growing resistance within contemporary practice to visual languages that aestheticise suffering. Many artists are consciously moving away from imagery saturated with violence or explicit trauma, seeking instead to articulate resilience through affirmation and care.

Nature plays a central role in this shift. Even stormy seas or winter landscapes can convey protection when approached with sensitivity. Akhonina’s work, for instance, often carries cultural memory through colour and atmosphere rather than symbol or narrative. Ukrainian visual traditions—rooted in land, seasonality and rhythm—find continuity within British and Welsh landscapes without being named directly.

This refusal of spectacle does not dilute meaning; it deepens it.

Environmental Context and Responsibility

Landscape art today also carries an unavoidable environmental dimension. Exhibitions staged within conservation settings introduce a different ethical framework—one where art exists not only about nature, but within it.

Akhonina’s participation in the Pensychnant Conservation Centre Open Art Exhibition exemplifies this alignment. The exhibition’s focus on nature, environment and conservation, coupled with charitable contributions from sales, positioned artistic practice as part of a broader ecological responsibility. For audiences, particularly in regions with strong local identities and languages, this integration of culture and care is deeply resonant.

Belonging Through Artistic Communities

While landscape offers solitude, artistic communities provide structure. For artists rebuilding their lives and practices after displacement, local societies play a crucial role in professional and emotional integration.

In London, organisations such as the Islington Art Society continue to offer precisely this kind of support. Akhonina’s active involvement in the Society—through exhibitions, plein air sessions and organisational participation—reflects how artist-led communities facilitate both artistic development and a sense of belonging. Membership in such societies is not merely honorary; it represents contribution, continuity and shared responsibility within the local cultural ecosystem.

Keeping Landscape Contemporary

Landscape is among the oldest artistic genres, yet it remains vital precisely because it adapts. Contemporary relevance lies not in novelty of subject, but in sincerity of vision.

Artists like Akhonina demonstrate that awareness of current discourse can coexist with a deeply personal visual language. Her use of colour—bold, affirmative and life-oriented—pushes against the austerity often associated with post-crisis aesthetics. The steady movement of her works from exhibitions into private collections suggests a wider appetite for art that offers restoration as well as reflection.

Why Landscape Matters Now

As more people renegotiate their relationship to place—through migration, environmental change or social instability—landscape art offers a rare form of continuity. It allows belonging without explanation and meaning without instruction.

Nature-driven abstraction does not promise resolution. What it offers instead is space: to observe, to breathe, to reconnect. Through practices such as those seen in Akhonina’s work, landscape becomes not an escape from reality, but a means of rebuilding it.

This is not a retreat. It is a reconstruction.